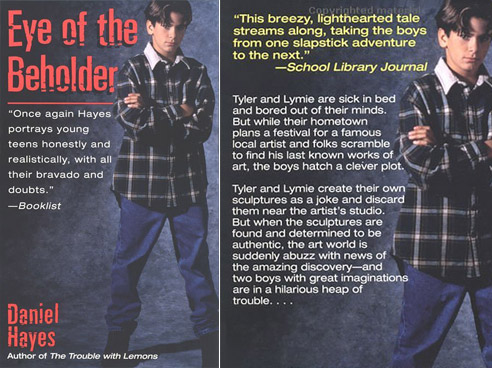

Eye of the Beholder

“(A) laugh-out-loud sequel to his excellent first novel.”

-VILLAGE VOICE

“Downright hilarious…Once again, Hayes portrays young teens honestly and realistically, with all their bravado and doubts.”

– BOOKLIST

“This breezy, lighthearted tale streams along, taking the boys from one slapstick adventure to the next.”

– SCHOOL LIBRARY JOURNAL

The Article that Inspired Eye of the Beholder

Eye of the Beholder was inspired by a February 1985 article in Parade Magazine. Click here to view a copy of that article.

Chapter One

Click here for printable version.

Almost four days to the hour after Lymie got there, I clocked him on the head with a book so humongous I almost wrenched my back throwing it. It was the blue medical book Mom had left on my nightstand, opened to the chicken pox page. Mom was pretty mad, so I didn’t even try telling her it was kind of her fault for supplying me with ammunition when she knew Lymie and I were fighting. Besides, she’d have just told me that nobody normal would ever even think of using a book as ammunition and that as soon as I got better we were going to have a serious discussion about things. And then she’d probably remind me that it was my idea to have Lymie stay with me in the first place.

Which it was. After three days of being sick alone, I was going crazy. I had a headache and chills and I was driving Mom up the wall with my whining (so she said) although I thought I’d been pretty good considering how lousy I felt and how I’d been cooped up all that time in a room by myself like some kind of prisoner. So when Lymie called to tell me he had the chicken pox too, the first thing I thought of (when I got done laughing) was that he should come over to my house and we could be sick together. Our mothers finally decided it was a good idea too. Then they could take turns watching us instead of them both being stuck with one of us full time.

Things were pretty decent at first. Mom had Chuckie, our groundskeeper, move the bed out of my brother Christopher’s room and put it up in my room. Then Lymie’s mother drove Lymie over and we were in business. As soon as everybody cleared out, Lymie dug this crumpled up piece of paper out of his pocket.

“Hey, Ty, listen to this,” he told me. “It’s from the nurse. It’s about you.” He started reading. Lymie speed.

“Dear Parents:

This is to alert you to the fact that your child has been exposed to chicken pox. If your child has not yet had chicken pox, he is…vul…vul something….”

I went over and sat next to him. “Vulnerable,” I said, looking at the word he was pointing at. He continued.

“Vulnerable. Initial symptoms include a low-grade fever, male…or maybe mal….”

I grabbed the note. “It’s malaise,” I told him and then kept reading it myself.

“Initial symptoms include a low-grade fever, malaise, and within twenty-four hours the appearance of a rash. Infected children must be kept at home for at least a week but may return to school as soon as all lesions are crusted; the crusts are not infectious.”

“Gross,” I said. “I’m not going back to school if I’m still all crusted.”

“Me either,” Lymie said. “We’ll have to keep acting sick until we look normal again.”

“You might never get to go back,” I told him.

Lymie clubbed me with his pillow. “You woulda never even started school if you hadda wait to look normal.” He paused for a second and thought. “What about malaise? You think we got that yet?” He lay back on his bed and looked up studying me.

I already knew “malaise” from seeing it in the medical book. I tried to look all serious. “It usually means you turn green and start barfing all over the place. People used to foam at the mouth when they had it, but that’s kinda rare now with modern medications.”

Lymie sat up and gawked at me harder than ever. “You’re kidding me, right?”

I kind of toyed with the idea of shrugging my shoulders and handing him the medical book so he could check it out himself, which he never would’ve done in a million years, but I didn’t. Lymie’s got this chubby, intense-looking face that gets all scrunched up when he’s worried, and it’s hard to put him on without feeling like some kind of lowlife.

“Nah,” I told him. “It just means feeling sick. You know, cruddy…lousy. Like we’ve already been feeling.”

“Thank God.” He clubbed me another one with his pillow and then he slumped back on his bed and took a deep breath. He looked so relieved I was glad I hadn’t lied.

The next few days chugged along pretty much like that. A lot of busting on each other and plenty of pillow attacks, but nothing major. Lymie and I watched about twenty movies on my VCR and played video games until we thought our wrists would fall off. Some of the time we spent telling each other how great our lives were going to be. I was going to be an actor like my brother Christopher and my mom, and I was going to work out with weights and do calisthenics till I was tough like Chuckie. Lymie would never admit he wasn’t tough already, so he didn’t say anything about working out. He thought he might want to be a director, but he wasn’t too sure. He was still going through that stage where he was thinking about maybe being a cop. Only he didn’t want to work for a police department or anything. He just wanted to do it on his own. Kind of like Superman or Spiderman but without the costume. I told him he could go by the name Spazman because that one wasn’t taken, and I cracked up. He did too. After he clubbed me again with his pillow, that is.

After forty-eight hours of this kind of thing though, the honeymoon was over. All the dumb things Lymie had a habit of saying–like his idea about being a supersleuth–were starting to grate on my nerves. And Lymie wasn’t exactly thrilled about me constantly pointing out to him just how dumb his ideas were. Not only that, but I require about twice as much sleep as Lymie, and it seemed like every time I dozed off, he’d whack me over the head with a pillow and ask me what I wanted to do. It never dawned on him that what I wanted to do was sleep. We were quite a team. Lymie was mad when I was sleeping, and I was mad when I wasn’t.

How I ended up clocking Lymie with the medical book was he woke me up for about the tenth time that day and I lay there smoldering, not looking at him or answering or anything. Then he got feeling sorry for himself and he said it. The same thing he’d been saying for days, and each time it made me a little crazier.

“If it wasn’t for you, I wouldn’t even have the chicken pox.”

“Lymie, you’re such a lamebrain!” I yelled, yanking up off the bed like I was on a string or something. “How many times have I gotta tell you? You didn’t get the stupid chicken pox from me!”

He didn’t answer because he knew what I was going to say next.

“Listen,” I told him. “You got the chicken pox the day after I did, right?”

Silence.

“Yes or no. You either did or you didn’t, right? So say it–yes or no.”

He sat there wearing that pudgy blank look he gets whenever he wants to shield himself from information.

“Yes,” I answered for him. “You got the chicken pox one day after I did. You can ask my mother. Ask your mother. Ask anybody!”

Lymie rolled his eyes. He knew the routine.

“And according to this book…” I picked up the medical book. “According to this book, chicken pox takes at least ten days to develop after you’ve been exposed to it. That’s incubation period, goofis, and it’s a scientific fact!”

Lymie leaned back on his headboard and took this smug-sounding deep breath. “So?”

“SO YOU DIDN’T GET THEM FROM ME!” I poked my head out toward him. “IT GOES AGAINST SCIENCE! WE BOTH GOT THEM FROM SOME INFECTED KID ABOUT TEN DAYS BEFORE WE EVEN KNEW IT!” I started waving the book around in the air as a kind of warning even though I knew that wouldn’t stop him.

“Then how come you got them first?” he said. “And how come the nurse sends home a notice warning us about you spreading diseases around the school?”

Unfortunately for Lymie, the book had been in the middle of a major wave in his direction when he finished, and all I had to do was crank on a little more steam and let it ride. He had just enough time to flinch back a few inches or it would’ve caught him right between the eyes. As it was, the book skipped off the side of his head and took the lamp off his nightstand.

By the time my mother got there, Lymie was bouncing up and down on top of me with his fingers twisted around my neck. He was so wrapped up in what he was doing he didn’t even hear Mom yelling. Of course it didn’t help that she was yelling my name, which she always does whenever we fight, same as Lymie’s mother always yells his name, no matter who’s getting strangled or belted at the time.

When Lymie finally realized Mom was in the room and he let go of me, the first thing he did was to start rubbing the side of his head. Then he went over and picked up the lamp and set it on his nightstand and put the medical book back on mine. That really ticked me off. I mean, if you’re going to rat on somebody, you should at least do it in words.

“Timothy Tyler McAllister,” Mom said, planting her hands on her hips and putting on this flabbergasted face, “did you throw that book at Lymie?”

“He was bothering me.” I started rubbing my neck where Lymie’d strangled me, hoping maybe I could land a little sympathy too.

Mom sat on my bed and looked at me for a second. Then she picked up the medical book, not like she was going to read it, but more like you’d heft a rock or something. Her other hand came up under my jaw and wrapped its fingers around my cheeks. Next thing I knew, the book was in my face.

“Look at this thing,” she said. “Are you trying to kill somebody?”

I looked at it. It was pretty huge. “I was just trying to make him shut up.”

I heard this big sigh come out of her. “You know what I think about hitting people.”

“You don’t believe in it,” I said and tried not to sound bored.

“And why don’t I believe in it?”

When I hesitated for a second, I could feel her fingers tighten on my jaw and the book started waving a little. “You don’t think it solves anything,” I told her.

“And…?”

“And you think it’s wrong and barbaric,” I said, rolling my eyes.

The fingers dug in a little. “Let’s not push our luck,” she said. Her other hand was waving the book harder now, like her throwing arm might be getting itchy. “Believe me, if I thought it’d do any good….” The book was bobbing around right in front of my nose. “But in this house we don’t hit–for any reason.” The book went down and she cranked my head around until we were eye to eye. “Do we understand each other?”

I kind of wanted to ask her about her views on strangling, for Lymie’s benefit, but her fingers were still locked around my cheeks and I could feel they wanted me to nod, so I did.

When Mom left, she took the medical book with her.

*****

That evening, Lymie’s father started coming over after he finished his farm work. Which was probably no big coincidence since I’d also noticed that Mom had Chuckie start painting the hallway right outside my room. Chuckie had been finishing up as much of the outside work as he could before the cold weather arrived, and the weather was still great, so that wasn’t it. I figured that moving him inside during the day, and bringing in Mr. Lawrence at night, was part of some kind of riot control plan.

“Why don’t you just send for Mrs. Saunders?” I said to Mom when I realized what was going on. “Next thing you know, you’ll be dragging people in off the street.” Mrs. Saunders was our housekeeper and she’d been visiting her sister in Burbank since a few days before I got sick. She’s one of the few people I know who doesn’t believe you can spoil a kid with kindness. Especially a sick kid. I’d already thought about calling her a few times and letting it slip how I was sick and miserable because I knew she’d come running.

Mom shook her head. “Do you really think it’s necessary to ruin the only vacation Mrs. Saunders has taken in over a year because we have two boys here who are too immature to share a room like two civilized young men?”

That’s the kind of question you can’t possibly say yes to without looking like an idiot. Besides, feeling guilty over maybe ruining Mrs. Saunders’s vacation was why I hadn’t called her myself.

“I was just thinking about you,” I said, kind of smirking to myself at how I’d gotten out of having to say no.

“That’s very kind of you, dear, but we’ll manage to struggle through this on our own.” And then she gave this sigh like maybe she wasn’t too sure.

I didn’t really see what the big deal was. Sure, Lymie and I fought some, but we weren’t all that bad. And our mothers weren’t all that defenseless either. Lymie’s mother alone probably could have put an end to World War II if she’d been there and it’d been bothering her. And if that didn’t work, my mother could have reasoned with the armies, telling them how on this planet we don’t fight, until they all decided it’d be easier just to forget the whole thing.

Lymie’s father didn’t seem too bent out of shape by having to be there. He’d sit on a chair between our beds reading his newspaper. Out loud. And looking for audience participation.

“Says here,” he told us one night in this hokey twang I was pretty sure he put on for my benefit because I’d never lived in the country before, “says here that two fellas robbed a convenience store in New York City and when they went to make their getaway, their car had been stolen.” He chuckled. “Now how about that?”

“City people,” Lymie sneered, leaning up so he could look right at me.

“Shut up,” I told him.

Mr. Lawrence kept chuckling to himself just like nobody’d even said anything. A few minutes later he came out with, “Hmm, now here’s something interestin’. Looks like we’re in for some big doings around here.”

“Yeah,” Lymie said. “Like what?”

“Well,” he said after he took his time and skimmed the article a little more, “remember that famous Eye-talian artist by the name of Badoglio that spent a few years in Wakefield as a young man?”

“Badoglio?” I said, sitting up. “Yeah, I heard of him. He used to do sculptures and stuff.”

“Some artist,” Lymie said. “He made ugly rock heads with big noses.”

Mr. Lawrence laughed. “What we consider ugly rock heads with big noses are considered valuable treasures by them that know art and understand it. I s’pose they see things in it the rest of us miss.”

“So what about the…the big doings?” I was hoping I wouldn’t still be all crusted over if something big was about to happen.

“Well, let me see,” Mr. Lawrence said. He rocked back in his chair and studied the paper some more. “Says here they’re planning some kind of festival in Academy Park to celebrate the centennial of Badoglio’s birth. They’ve got a traveling Badoglio exhibit coming in. There’s a whole schedule of events here. There’ll be art critics, a crafts show, activities for the kids, food booths….”

“Food booths?” Lymie said, perking right up.

“Your stomach is really artistic, Lyme,” I said.

“Shut up,” he told me and leaned over behind his father and tried to belt me. I scooted to the far side of the bed.

“Hey, boys, I’d forgotten about this part,” Mr. Lawrence continued. “Listen to this:

Legend has it that in 1912, in a fit of depression, the highly emotional young Badoglio rushed out of his house in the middle of the night and threw two of his partially completed heads into the Hoosickill River. Next Saturday, a week before the celebration, the section of the Hoosickill in the vicinity of Badoglio’s former house will be dredged in the hope of finding one of these lost treasures.

He closed the paper and looked up beaming. “That’d be something, huh, boys? Wouldn’t that put Wakefield on the map if they were to find something?”

“Are they gonna have food booths at the dredging?” Lymie wanted to know.

*****

Mom came in and made us turn out the lights at ten o’clock. For once I wasn’t tired.

“That’s pretty neat, Lymie. You know, about that Badoglio guy. You think he really did chuck those heads in the river?”

“Probably,” Lymie said. “Who’d make up a story like that?”

“But why? After all the work he must’ve done on them?”

“‘Cause he knew they stunk,” Lymie said.

“Come on, Lyme. They couldn’t have stunk too bad if they’re considered valuable treasures now.”

“Tyler, did you ever see that guy’s work?”

“No.”

“Then don’t tell me they don’t stink. We used to have to look at pictures of that guy’s stuff in art class and I’m serious, he couldn’t chisel his way out of a paper bag.”

“Maybe you just don’t undestand art, like your father says.”

“Maybe not. But I understand ugly, and any rock that guy ever touched turned out ugly, believe me.”

“I’d still like to see some of his stuff.” I’m always curious about things like that. I even watch public TV sometimes when Lymie isn’t around.

“You sure you want to see it?” Lymie said. “Knowing you, it’ll probably give you nightmares.”

“Funny, Lyme,” I told him, “but I’ll worry about my own nightmares.”

“Yeah, well don’t say I didn’t warn you. I’m telling you, Ty, the two of us could make better heads than that guy did.”

If I had an alarm in my head that’d go off every time I heard something that could lead to serious trouble, it would’ve been ringing like crazy right then.

But I didn’t hear a thing.