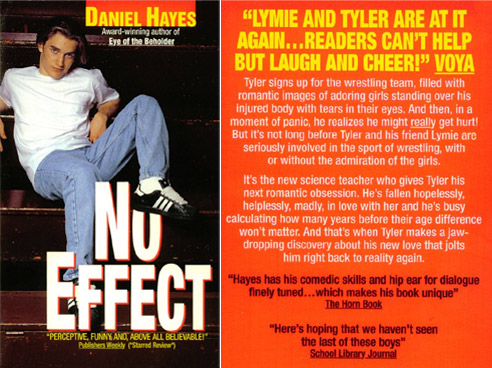

No Effect

“Hayes masterfully blends humor and heartache…Perceptive, funny, and, above all, believable…The author’s steady hand allows the reader to see serious or disturbing events for what they are — part of life.

– PUBLISHERS WEEKLY (Starred Review)

“Here’s hoping that we haven’t seen the last of these boys.”

-SCHOOL LIBRARY JOURNAL

“Hayes has such a sure touch he can make 13 year-old-boy humor hit your funny bone, even if you’re not a 13 year-old boy.”

– VILLAGE VOICE

Chapter One

Click here for printable version.

There were a ton of reasons why I shouldn’t have gone out for wrestling. Even before I found out the Coach was some kind of lunatic. For starters, I’m not all that tough. I’m a good runner and I’ve always kept myself in decent shape, but those things didn’t seem to help much when it came to fighting. In the past year alone I’d taken a few pretty good beatings from kids and the thought crossed my mind that wrestling could end up being nothing but a way for me to have regular beatings built into my schedule. And I wasn’t thrilled about the idea of putting on that goofy-looking protective headgear they make you wear-probably because some wrestler once had his ears ripped off or something. Plus I’d always heard that wrestling coaches make you lose about fifty pounds right off the bat. Which meant I’d be wrestling toddlers.

But none of these thoughts really sunk in. I still went out for wrestling.

I hadn’t given it that much thought beforehand. After all, eighth graders don’t usually get to go out for any high school sports. So it came as kind of a surprise in music class that afternoon when Mr. Blumberg got on the P.A. and announced that they needed more kids for the wrestling team, especially lightweight kids, and that anybody who wanted to, even eighth graders, could try out. All you had to do was get a permission slip and a physical.

Mr. Blumberg no sooner got done announcing this than a folded up piece of paper came flying across the aisle and skipped off my desk and onto the floor. It was from Lymie. Music, which we only have twice a week, and art, which we have the other three days, are the only classes besides gym that Lymie and I are together in. In most of my classes I’m accelerated. In music and art it doesn’t matter we’re all pretty much remedials there.

I checked for Mr. Fritz before I reached down to grab the note. He was resetting the needle on Haydn’s Surprise Symphony. He looked kind of annoyed because he’d just given us this whole spiel about how Haydn had stuck a surprise in the symphony to keep everybody in the audience awake, and Peter Kawecki had asked him if Mr. Blumberg’s announcement was the surprise. Mr. Fritz didn’t even answer. He just frowned and concentrated on resetting the needle without scratching the record.

After the music started up again, I worked the note in closer with my foot until I could grab it, and then I opened it behind my pile of books. It said, “Hey, Ty, you going out for that?”

I had to smile. I mean, who else but Lymie would start a note with “Hey”? When I looked up, I noticed Mr. Fritz was smiling at me and nodding his head. It took me a few seconds to realize that the violins had all of the sudden gotten louder, which was the surprise, and Mr. Fritz must’ve thought that my smile meant that I got a kick out of it.

As soon as Mr. Fritz closed his eyes and seemed to go back into his own little world, I looked over at Lymie’s chubby, expectant face and shrugged. Lymie grabbed another scrap of paper and started in on it. The way he was hunched over the desk with his face all scrunched up, you’d think he was writing a novel or something. He folded the note, did a quick Fritz check, and flicked it at me. This time it said, “You’re scrawny enough.”

I looked back over at him. He was all cracked up.

“Moron,” I whispered across the aisle. “Butthead” Then my mouth froze in its tracks. Mr. Fritz had picked the needle off the record, and I was waiting for him to start yelling at me for talking.

“Wasn’t that a surprise, boys and girls?” Mr. Fritz said in his still-in-his-own-little-world voice. “Imagine someone about ready to drift off right there in his seat and ‘bang’ that crescendo of violins. Let’s play that again.” He bent down to reset the needle.

Lymie grabbed some more paper, scribbled down something, and flicked it at me. This one said, “Were you just talking to yourself?”

I looked at him. He was all cracked up again and pretending to thump on his desk. I smiled and leaned back in my seat. I had some serious thinking to do.

There’s two sides to any argument. I went over the plus side of wrestling first.

To start with, I could get a letter. And getting a letter in eighth grade, that’d be nothing to sneeze at.

Second, it’d probably make me stronger. I’d always wanted to be better in the strength department, and wrestling would give me a pretty good workout every day.

And there was a third reason. It was nothing more than a daydream really, but I’m pretty sure it was the thing that sold me on the whole idea. All the rest of the afternoon, whenever I’d think about being on the wrestling team. I’d get this picture in my head, like a recurring vision or something. I’d see myself lying on the mat, pretty much unconscious, but not completely. I’d be delirious and everything, but some part of me would still be able to see what’s going on. And what’s going on is that all the girls in the stands are going crazy because they’re afraid I’m not going to be all right. And while the coach is lifting my head trying to get me to come to, and while the team doctor’s trying to get a pulse on me, I can see all my teammates looking worried and beating their fists into their hands and swearing what they’ll do to the other team if one hair on my head has been harmed. After a while, the coach and the team doctor hoist me up and start to lead me off the mat. The crowd is going crazy cheering. The girls in the stands are jumping around, and I notice most of them have tears in their eyes. Before I leave the mat, the referee comes over and lifts my arm in the air, and I hear the announcer telling everybody that I’m the winner because the kid I was wrestling had done something illegal, which was the only reason I got hurt in the first place. Then I’m helped into the locker room for medical attention. And even after the door closes behind us, I can still hear the cheering.

Of course, even while I was having this vision, some other part of me started shouting “Baloney!” and telling me all the reasons why I shouldn’t go out for wrestling. First of all, I might really get hurt. Sincerely. Broken bones were a real possibility, and hernias, and brain damage, the list went on and on. And team doctor? Like they were going to go to every wrestling match and wait for somebody to get hurt. That only pays for the big spectator sports like football, or maybe basketball. Which leads us to the cheering crowds. Any dimwit knows that unless you’re in the Olympics or something, wrestling crowds consist of a few parents and a couple of kids who probably missed their bus. And girls? What kind of girls go to wrestling matches anyway? Girls who like violence? Or maybe emotionally disturbed ones who get their jollies seeing you get stuck in some kind of crazy python hold that’d probably prevent you from ever having kids unless you adopted some. Which led my mind to remind me of my main fear: humiliation. Every sport, every activity even, has its humiliation potential, but wrestling’s got to be the big daddy of them all. There you are, out there all by yourself in tights (they’re kind of like tights anyway) with some guy you don’t even know trying to twist you into funny pretzel shapes for the amusement of some crowd. Only it’s not a crowd. Luckily.

My mind struggled with all this for the rest of the afternoon. Once I almost decided to chuck the whole idea. Then all of the sudden there it was again, my vision. Bigger and better than ever. I’m being led off the mat. Women are going crazy. Not even girls now. Real women. And not disturbed ones either. Nice, normal women who are all beautiful. And they’ve all got tears running down their faces. And every tear has my name on it.

I grabbed a permission slip off the office counter before I went home.

“Case closed, Tyler. The answer is no.”

I followed her into the kitchen. I didn’t have any real game plan. It was only a week ago that I’d gotten in pretty bad trouble over something Lymie and I did that was supposed to be just a little joke but kind of backfired, so I knew I wasn’t in any great bargaining position. I figured my best bet would be to try to wear her down with whining.

“Why not, Mom? You can’t just say no like that without even discussing it.”

Mom planted her feet and looked me in the eye. “I think we’ve had enough trouble with you and fighting. And as far as I’m concerned, wrestling is another of those sports that sanctions and glorifies combat. Not only am I opposed to the idea philosophically, but I think it’s dangerous. I’m not going to let you do something where I’ll have to worry every minute that you’ll get hurt.”

“Mom,” I said, “listen to reason, will ya?” I cut around in front of her as she headed for the cupboard. “Did you ever hear about something terrible happening to a wrestler; like he got hurt really bad or dropped dead on the mat or something? You always hear about things like that in football. And boxing, sure. And even in basketball sometimes somebody’ll drop dead in the middle of the game. But wrestling, Mom? Be real.” I stuck my face in front of hers. “Come on. Look me in the eye and tell me you’ve ever heard of anything like that happening to some wrestler.”

“No,” she said, staring me right in the eye. “And that’s no on the permission slip too.” She yanked her face free and brushed past me.

“Maybe you’re thinking of professional wrestling, Mom. You know Lex Lugar, Damian Demento; guys getting hit with tennis rackets and stuff.”

“No, I’m not,” she said as she rummaged through the cupboard. “Case closed.”

“I think we need a little objectivity here,” I said and grabbed the phone. “Chris’ll talk some sense into you.”

I heard Mom give this big sigh as I dialed my brother’s number. I got his answering machine and remembered it was still the middle of the day in Los Angeles. So I dialed Chuckie’s number. Chuckie’s our groundskeeper, and you can tell just by how he’s built that he’s into sports. I’d seen him going into his cottage on the far side of our property when I got home. Almost before he got to say hello, I started in on him, telling him about Mr. Blumberg’s announcement and how wrestling could help build up my strength and earn me a letter and everything. When I was done, he said, “Sounds great, Ace.”

“Yeah, it would be,” I told him,”only I can’t get Mom to sign the stupid permission slip. You gotta talk to her, Chuckie. Tell her how good it’ll be for me.”

“No can do, Ace. I just work here. I’m not gonna start telling your mother how to run her house.”

“How to run her house!” I squeaked. “Chuckie, what are we talking about here, choosing curtain colors? This is my life!”

“Sorry, pal. But you’ll have to work this one out on your own.”

“Chuckie, it’ll take like two seconds. Just tell her she’s being foolish and to sign the thing. I’ll put her on.” I started to wave Mom over.

“I gotta go, Ace. My phone’s ringing.”

I heard a click. Right after a chuckle, which was because he knew I knew he didn’t even have call waiting. I looked at Mom. Her arms were folded and she was kind of hunkered down, ready for anything.

“Yeah, that’s what I tried to tell her,” I said into the phone. “It’s the safest thing in the world. Huh? Oh, yeah, I know how women get. Yeah, you’re probably right. She’ll probably come around on her own. Okay, yeah. Thanks, Chuckie.”

I hung up the phone. Mom came sashaying over to me, clamped her thumb and forefinger around both sides of my jaw, and squeezed. “No,” she said right in my face. “No, no, no.”

I looked at her. And it finally dawned on me. She’d really made up her mind. I’d lost. It didn’t matter what I did. I could kiss my letter good-bye. I could kiss my recurring vision goodbye. Suddenly I felt sad.

“Fine, Mom.” I pulled my jaw free and started to leave. “Forget it.” And then in the doorway I turned to her. “You know, Mom, it’s not fair. Seriously.”

She had her arms folded again. And she was hunkered down again.

“Other kids probably have mothers who won’t sign their permission slips either,” I said. “But they just go to their fathers to get ’em signed. But I don’t have a father.” I looked her right in the eye. “And that’s not fair.”

I had to get out of there quick. I thought I might start crying.

Before dinner I heard this little knock at my door, and Mom came in holding the permission slip.

“I signed it,” she said and handed it to me.

I sat up on my bed. I felt strange. Bad strange. It’s funny, I try all kinds of things to get what I want, and what I’d said downstairs was the God’s honest truth. And yet I felt guilty. Like I’d cheated or something.

“I’m sorry I said that,” I told her.

“I never would have signed it,” she said, pointing at the permission slip. “Partly because I don’t like fighting, but mostly because I’m scared to death you might get hurt. But your father loved sports, and you’re right, he would have signed it.” She walked over to the door and stopped. “And he would have done his best to be there for you at every match.”

I sat there holding the thing in my hand until Mrs. Saunders called me down to dinner.

The physical was the last step. And the coldest. It must have been fifty degrees in the nurse’s office. Of course, it’s hard to feel all cozy and nice when you’re standing around on cold linoleum in nothing but your underwear. It was make-up day for winter sports physicals, so there were only five of us lined up in front of the doctor. The nurse was behind us at her desk facing the other way. I wondered if she was checking us out whenever nobody was looking. I know if there were girls behind me getting physicals, I’d be sneaking peeks like crazy.

But freezing in my underwear around some nurse who might be a Peeping Tom was the least of my worries. All the other kids were clutching their permission slips. I had a permission slip plus a stack of medical records I could’ve knocked out a moose with. Mom’s idea. Or more like Mom’s orders. She thought the doctor should know about my allergies, and my asthma, and my history of migraines, and how I’d dislocated my shoulder when I was eight. I even had a record of all my shots, maybe in case I bit somebody or something. I was afraid the doctor would take one look at my medical history and tell me to hit the road.

Somebody bumped me from behind. Then I heard this voice say. “Hey, John Henry, you gonna wrestle or play basketball?”

It was the big guy in back of me, Ox Bentley, our star linebacker during the football season. I didn’t know him personally or anything, but everybody knew who he was.

Next something thumped me between the shoulder blades.

“Hey, John Henry, you deaf or something?”

It was Ox again. And he’d been talking to me. I looked at him. “I’m not John Henry,” I said. I tried to say it nice. When football players, especially seniors, start talking to junior high kids, it usually spells trouble.

“Isn’t that your name?” He pointed to my waistband. “John Henry,” he read slowly.

I looked at him again. I couldn’t tell if he was putting me on or not.

“No,” I said. “That’s just the manufacturer.”

That cracked him up. “You’re all right,” he said, clapping me on the shoulder. “You’re all right, John Henry.”

Just then the doctor finished with the kid ahead of me, a kid Ox probably called Hanes. I stepped forward and handed him my papers. He tossed them on the table behind him, cranked my head around, and shined a light in my ears, first one side and then the other. Next he listened to my heart for a minute. Then he did it. I knew he was going to, but I still wasn’t ready for it. He pulled my waistband out, reached in, and came up under my left gonad. I took a hitching breath as he applied a little pressure.

“Cough,” he said, and pushed my head sideways with his free hand.

I did it.

“Again,” he said, coming up under the other one. I did it again.

He pulled his hand out and rapped me on the arm.

“Next,” he said.

And that was it. I swear to God, you could have cancer, rabies, bubonic plague, and two broken legs, and you’d pass a school physical if your ears were clean, your heart was beating, and you had a couple of cojones that felt halfway decent.

So I was in business. I was now officially ready to wrestle. And I felt pretty good about it. It wasn’t only the women in the stands part. I knew that was just my imagination working overtime. And it was more than getting a letter, or building up my strength, or anything like that. It was, I don’t know, a feeling like I was a part of something bigger than myself. And that no matter how tough it was I still knew that I was part of a bunch of guys working together for one common goal: victory. Like guys going off to war, only we wouldn’t have to kill anybody, just pin them. It was a good feeling, a feeling of belonging, with maybe a dash of prestige mixed in. I noticed as I was walking out of the school with Lymie that I was even walking a little straighter, a little taller. I was part of a team-a real high school team.

“So you’re really gonna do it?” Lymie said. “You’re really gonna wrestle?”

I looked at him. And I tried not to seem too proud, too smug. “Yeah,” I said, “I’m gonna do it.”

Lymie looked back at me. “Whaddaya wanna spend your free time rolling around the floor with a bunch of guys for?” He shrugged and started for his bus.

I stood there. I didn’t grab him or argue with him. I didn’t even call him anything. I just stood there and felt all that sense of belonging to something bigger than myself-with maybe a dash of prestige mixed in-schlump back to wherever it hides most of the time.

“Later, Ty,” Lymie called back over his shoulder.

“Yeah,” I told him, “later.”

This is the end of Chapter One, No Effect.

An Avon Flare Book

Published by arrangement with David R. Godine, Publisher, Inc.

Copyright 1994 by Daniel Hayes