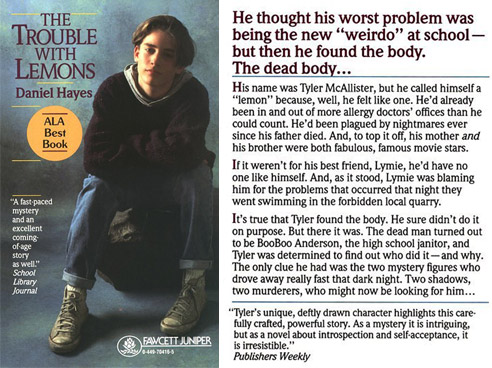

The

Trouble

With Lemons

“Tyler’s unique, deftly drawn character highlights this carefully crafted, powerful story. As a mystery, it is intriguing, but as a novel about introspection and self-acceptance, it is irresistible.”

– PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

“Self-acceptance, the vagaries of human nature, finding one’s niche in the world — all wrapped in a blanket of mystery involving a body in a local quarry — make up the elements of this fine novel by a promising new author… suspense holds up to the very end.”

– THE HORN BOOK

TEACHERS, click here for a free The Trouble with Lemons teacher’s guide from Random House.

Photos of the Quarry that Inspired The Trouble With Lemons

These are photos of the actual stone quarry in upstate New York that inspired The Trouble With Lemons.

The ladder and raft visible in these pictures weren’t there when the story took place. These structures

were added during the 1990’s when the quarry was open to the public for a while.

Chapter One

Click here for printable version.

Lymie told me we’d be sorry if we went. Which I didn’t listen to, seeing how Lymie was the kind of kid who thought you’d be sorry if you got out of bed in the morning. Besides, nobody ever really listened to Lymie. Not even Lymie.

But this time he was right.

I suppose it had to happen sooner or later, Lymie’s being right, that is. It’s the law of averages or something. And it didn’t surprise me that in Lymie’s muddled-up mind, his warning me proved that all the trouble that followed was my fault. Of course he doesn’t say how it was his idea to go swimming, not mine, and if we’d stayed out of the water, nothing would have happened. At least not to us.

Sure, it was my idea for us to sneak out to the quarry that night. But only to see it. Period. I’d discovered the quarry by accident a few weeks earlier and it was wicked cool, this huge basin of gray-green water sitting there in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by these solid rock walls like a miniature Grand Canyon or something. I couldn’t believe my eyes. It was the kind of place part of you’d like to keep all to yourself, but another part of you’d like to bring all your friends to. Only since we were hardly a week into the new school year, and since school was already out for the summer when I moved to Wakefield, and since I’m kind of quiet anyway, all my friends stood for Lymie. And if it wasn’t for Mom, I wouldn’t’ve even had Lymie. She’d met Lymie’s mother at the Wakefield library one day and after that we used to drive out to this farm she lived on for fresh eggs and milk and stuff. And this lady just happened to have a kid my age, and Mom just happened to invite him over all the time. I knew it was a setup because Mom is one of these lowfat, low-cholesterol people who wouldn’t be caught dead eating an egg, and any milk my family used was bound to be skim.

It worked though. Lymie and I did end up being best friends. But not right off the bat. And it wasn’t easy. For starters, Lymie and I are like total opposites. I’m a city kid; Lymie’s a farm kid. I’m on the thin side; Lymie’s on the chubby side. I’m a strict vegetarian; Lymie thinks real men eat cows and pigs and stuff. That kind of thing. But the real problem was Lymie’d always do a million things that’d drive me crazy. Like if he’d see a Porsche or something, he’d make barfing noises and go, “Piece of foreign junk,” even though he knew my brother had a Porsche. And if he saw a Trans Am or something jacked up in the back so high it looked like it was getting ready to do a headstand, he’d whack me in the arm and go, “You wanna see a car? Now there’s a car.” Early on, about the only thing we agreed on was that at least a couple of times a day we’d have to try to punch each other’s faces in.

Still for some reason our mothers seemed to think we’d be good for each other.

I asked Chuckie about the quarry (Chuckie’s our groundskeeper), and all he told me was to stay away from the place or I’d probably end up drowning because the water was about fifty feet deep all across it. And if I didn’t drown, he told me I’d get arrested for trespassing. Big help. Lymie was no better. He’d never even seen it. That really blew me away, him having lived in Wakefield his whole life. Talk about not taking an interest in your environment.

The quarry wasn’t much more than a mile from my house and I’d walked there alone quite a few times. They had signs stuck up all over the place warning you to keep out unless you wanted to get prosecuted, and every once in a while somebody did. A couple of nights after I found the place, the Miller sisters were arrested there with two college guys. They were all in the water swimming away and when the cops pulled in with their spotlight and told them to get out, they did. Only according to the two deputies, they weren’t wearing anything and the girls started doing like a hula dance or something right on the rocks. In the spotlight. Everybody was talking about it. Their father was some big minister who’d run for the school board because he said there were dirty books in the school library (Lymie checked and couldn’t find any), and everybody said he almost busted a blood vessel. He even tried to get the cops fired for not turning off their light.

That story didn’t mean much to me, not really knowing these people, except it got me thinking about checking out the quarry at night. Places are different at night, and a place that beautiful in the daytime would probably knock your socks off in the moonlight. But having been raised under streetlights, I’m no Daniel Boone, and traipsing through the wilderness at night wasn’t something I was about to do. Not alone anyway.

That’s where Lymie figured in. Even though he moans and complains, it’s usually not so tough for me to get him to do what I want. I knew Lymie was staying over that Saturday night so I slept in that morning like I do on New Year’s Eve or any other day when I know I’ll want to stay up late. And as soon as Lymie got there I started building up the place, painting this cool picture in his mind. Plus, I reminded him about the Miller Sisters’ episode. With Lymie’s mentality, something like that elevated the place to a historical landmark practically. It didn’t hurt either, my telling him that our housekeeper, Mrs. Saunders, was a heavy sleeper. She wasn’t really. But she was kind of heavy. And she would be sleeping.

“It’s almost midnight,” Lymie had said for about the hundredth time after we left my house. “I must be crazy.”

“Yeah, what else is new?” I said finally, backpedaling and watching Lymie chug along, his pudgy face all scrunched up with effort. Between complaints he’d click his tongue and burp. Lymie was always snorting or belching or something, like he thought the whole purpose of his head was to make goofy noises. He’s kind of a funny kid.

Passing the last streetlight on the edge of town, we took a left into the shadows and hopped a gate into this huge pasture. With the moon almost full, seeing was no problem. I followed a zigzaggy cow trail, watching my step closely to make sure I didn’t step in something some cow might have left behind. I could hear Lymie muttering and snorting and clicking right at my heels. Pretty soon I slipped through a barbed fence on the other side. Nothing but a bunch of brush and some bushes separated us from the quarry now.

“Okay, Lymie, you gotta be quiet till we make sure nobody’s there.”

“Yeah, Tyler,” Lymie sputtered as I tried to unsnag his shirt from the barbed wire, “like the whole stupid world is probably climbing out of bed in the middle of the night and ripping its clothes to get to this stupid place. Duh!”

Lymie always said “duh” when he thought I was saying something dumb. He said it quite a bit.

I started down the narrow path, probably an animal path or something, that led to the water’s edge. The brush was alive with mysterious squeaks and twitterings and buzzes. I stood still for a second and pricked up my ears. I could make out the sound of crickets and a few tree toads maybe, but that was it. The rest was pure mystery, like we were surrounded by some kind of strange and secret world out there in the shadows. I felt kind of like Alice in Wonderland or something (if she’d been a guy).

“Lymie,” I whispered. “Listen.”

Lymie let out this big belch. Then I could hear him scratching himself.

“Listen to what?”

I remembered who I was talking to.

“Forget it,” I told him.

“Forget what?” he said. “First you get all spastic and act like you heard something and then you say forget it.”

“Just shut up, Lymie.”

“You’re the one that started talking, dirtbag.”

That’s the kind of exchange that might have led to us punching each other out earlier in the summer, but we hardly ever did that any more. Lymie didn’t notice the same things I did. That’s all there was to it. And it wouldn’t matter if I hit him over the head with a two-by-four.

We tiptoed forward and before we knew it the path opened into a clearing, and we could see the water. A slight breeze blew our way, and you could tell by the sound of the leaves around us that they were getting ready to change color. They were drier and rustlier than a month ago. And the moon made one of those rippling orange ribbons that stretched from one side of the water to the other. I held my breath. It was beautiful.

I turned to see if Lymie appreciated any of this and was surprised to see he was all wide-eyed. In fact, you’d think he’d just inhaled a fly or something. I looked where he was looking. Across the water on the entrance lane, less than a hundred yards from where we stood, was the lighted red interior of a car. The light hadn’t been there a few seconds ago. A guy in a dark jacket climbed into the driver’s seat. Another figure sat on the passenger side. Before I could make out much else, the door slammed, plunging the car into darkness again. The engine rumbled, a big V-8 from the sound of it, and the car peeled out, splattering pebbles across the water. Tires screeched as the car skidded onto the highway. Finally the headlights came on, flashing like a strobe light through the trees as the car sped toward town.

“I wonder who that was,” Lymie whispered.

“Beats me,” I said. “It’s kinda weird how they took off like that. Maybe they saw us. You think?”

“Yeah, Tyler, real smart. Like they’re old enough to drive and they’re gonna panic when they see a couple of eighth graders sneaking through the bushes. Duh!”

“They don’t know we’re eighth graders, cow breath.”

“Oh, yeah, Ty. I forgot how big and tough you look in the dark. We’re lucky they didn’t have heart attacks right on the spot. We coulda got sued.”

He laughed and shoved me to the side in case I might have forgotten he was stronger than me, something Lymie always had to prove. I jabbed at him but without much interest. Big deal, so he thought I was scrawny. I was a runner like my brother Christopher, and no runner in his right mind wanted to be built like Lymie. He might not be what you’d call fat, but he was a little too close to it for my taste.

I sat on the rock ledge dangling my feet over the water. Lymie did too. We were quiet for a long time, looking around and listening to make sure we had the place to ourselves. Gradually I relaxed enough so I could start soaking up the atmosphere. Lymie fidgeted.

“Hey, Lymie,” I said, feeling like I had to entertain him, “I’ll show you where I scratched my name on the rock wall. It’s right under us.”

“Boy, Ty, you really know how to show somebody a good time.”

We rolled to our stomachs and peered down the side of the rock wall over the water. Lymie struck a match and immediately let out a whoop. Etched in big upside-down letters I saw:

T. Tyler McAllister

and under that, or over it, I guess, in big scribbly letters:

SUCKS

“Oh, no,” I moaned. I swear to God you could carve your name on the inside of a double-locked cast iron safe and when you opened it back up somebody’d have written something nasty about you.

“Whoever did that must know you,” Lymie said, elbowing me and yukking it up for all he was worth. “‘Cause they sure got the facts right!”

“Don’t be a jerk, Lyme,” I told him.

“Hey, I’m not the jerk,” he said laughing. “You’re the one who got caught taking a snooze in Old Lady Waverly’s class the other day, not me. My whole bus was talking about it.”

I groaned, remembering for the thousandth time how it felt waking up eye to eye with Old Lady Waverly, and everyone in the class giggling and gawking at me. It was like waking into a bad dream. My first week at a new school and already I looked like a total spazola. Exactly the kind of think Lymie would find amusing.

“You’re pitiful, Lymie. You can’t appreciate anything unless it’s totally stupid.”

“Why do you think I hang around with you?” That cracked him up all over again. “Boy, everybody said Old Lady Waverly really went hyper. It must have been great.”

“Yeah, Lyme. I’m real sorry you had to miss it,” I said sullenly.

Finding a rock, I began scratching out somebody’s lame excuse for a joke. Lymie lit matches for me and kept up with the stupid cracks. I scratched out a large area surrounding my name so it’d be harder for anyone else to add their two cents’ worth.

“So, Ty, when is Chris coming here again?” The last match flickered out and Lymie rolled to his back and stared up at the stars.

“I don’t know.” I chucked my rock into the bushes, hard, and turned to my side. “Not till Thanksgiving probably.”

“And your mom?”

“In a few weeks maybe. Depends how her shooting schedule goes.”

“Awesome,” Lymie said. “I can’t believe I actually know two movie stars. Me…Lymie Lawrence.” He grabbed his head. “Then again, why not me? I’m good looking. I’m bright. I’m…”

“You’re an idiot.”

“I’d like a second opinion.”

I knew he was waiting for me to say he was ugly too, but I wasn’t in the mood to play along. Sometimes I wished my mother and brother did something normal for a living like delivering mail or teaching school. Something where you didn’t have to constantly trek all over the planet. It was the same with my father when he was alive. Only he was a producer.

I hadn’t seen my mom or Chris since last month when I was in the hospital with a concussion. I’d been sleepwalking and fell down the stairs. (The doctors said that was a first.) Christopher came all the way from our old house in Los Angeles and Mom came all the way from where she was shooting on location in Colombia. First thing Chris said when he saw me was, “I told Mom we should make you sleep on a leash, Timmy Tyler, but she said your head was unbreakable.” Mom had poked him in the side and said, “Now don’t you pay any attention to him, Tyler,” but she knew I didn’t mind the teasing.

I answer to a lot of different names. See, Mom wanted to name me Tyler after her favorite uncle, and Dad had insisted on Timothy because he didn’t like the name Tyler. Or Mom’s favorite uncle either. So I ended up with both names. Mom and Mrs. Saunders called me Tyler (when they weren’t calling me “lamb” and “doll” and that kind of thing), and my dad called me Timothy, and Chris, being in the middle, called me Timmy Tyler. Dad and Mom had already separated before I started school, and Mom put me down as T. Tyler McAllister on all my school records. So that’s what I am officially.

“Hey, Ty,” Lymie said, climbing to his feet. “Cut the moping act and let’s go swimming.”

I sat up and thought for a second. It wasn’t really warm enough, but seeing how I’d dragged Lymie there, I said okay. We were both decent swimmers.

Lymie hopped out of his clothes and took a running leap into the water three feet below. Bobbing to the surface, he yelled, “This is great!” but knowing Lymie he would have said that if his head had smacked into an iceberg. I was freezing before I was half undressed, so I whipped off the rest of my clothes and dove in before I had a chance to change my mind.

The shock of the cold water took my breath away and made me a little spastic for a few seconds. I knew pretty soon my teeth would start chattering like crazy. That’s something that happens to skinny kids. Lymie could be packed in ice for two days and not get cold.

I warned Lymie not to swim too far from the low rocks about twenty feet to the right of where we’d dove in. That was one of the few places you could climb out without a long struggle. After all, we were naked. What if girls or cops or somebody pulled up in a car? I didn’t feel like putting on a show like the Miller sisters.

As usual Lymie ignored me, but I paddled toward the low rocks. When I was close enough for a quick getaway, I rolled onto my back and floated. Kind of. If I didn’t kick or stroke every so often, I’d sink like a rock. That’s another advantage Lymie had. He could float on his back for a week without so much as wiggling his ears.

I was really getting into the silky cool feel water has when you skinny-dip, staring at the moon, letting my mind drift. Suddenly I felt something sliding down my back.

“Watch it, Lymie, you weirdo.”

“What’s your problem now, hyper-spaz?”

A shiver shot up my spine which seemed to lift my hair. Lymie’s voice was in front of me and quite a ways off. I lay frozen for a few seconds, afraid to move, praying that some big friendly fish was getting into rubbing my backside. Then, taking a deep breath, I flipped to my stomach. My hands pushed into a heavy, wet, woolly thing. As I instinctively thrust the thing away, something rose up out of the darkness into the moonlight. And I saw it.

A face, pale and bloated. And hands, slimy hands reaching for my throat.

I jabbed at it. I kicked at it. I felt the bone on bone of my elbow on its head. As I broke away something slid down my stomach and I came up hard with my knee, so hard my head went under. My feet pushed off it and I came up screaming.

“Lymie! Lymie! OH MY GOD, LYMIE!”

I might have screamed out of control for a week if I hadn’t sucked up a mouthful of water. Gagging, I beat a hysterical path toward the shore until my head bashed into the rock ledge. I clawed my way over the bluff, scraping elbows and knees, and flopped belly down on the cold rock platform, choking and gasping for air. Cold water pumped painfully out my nose, and I thought I’d suffocate for sure. My head throbbed and my heart pounded against my rib cage.

Something touched my shoulder and I almost left my body.

“Tyler, you all right? Come on, can you breathe, man?” Lymie was out of breath and his voice trembled.

“Did you see…” I gasped, my chest heaving in fits and starts. “Did you…”

“Shut up!” Lymie yelled. “I saw it. Just breathe, will you!” He yanked me up and shook me like a rag doll. He probably thought I was having one of my asthma attacks.

“I almost drowned…It was grabbing at me!”

“Shut up, Tyler. Just breathe!” Lymie sounded like he wanted to cry, but by now I was crying enough for both of us. He tugged my arm. “Come on. We gotta get dressed and get out of here.”

My teeth jackhammered away as I struggled into my clothes. I kept peeking back at the water, half expecting something to crawl out. I felt my shirt rip as I tried to jam my wet arms through the arm holes. Lymie finished getting dressed and leaned over the ledge.

“I can see it, Ty. Under the water. Come ‘ere.”

Dropping my other sneaker, I crept up beside him. As much as I dreaded it, I knew I had to look. Maybe I had to see for myself that the thing was dead and powerless. I gasped when I saw it, a man, floating at an incline with arms and legs outstretched, like a freeze frame of a hopping frog.

Then I threw up, right into the water. Lymie held my belt so I wouldn’t fall in. He didn’t need to worry. There was no way I was going back in there.

This is the end of Chapter One, The Trouble with Lemons.

A Fawcett Juniper Book

Published by Ballantine Books by arrangement with David R. Godine, Publisher, Inc.